Exploring the Rich Legacy of Teochew Guildhalls: Bridges of Culture and Commerce

Guildhalls, dating back to the urban landscape of China during the Ming and Qing dynasties, were feudalistic organizations composed of people from the same hometown or profession. The earliest known guildhall, the Wuhu Guildhall in Beijing, dates back to the Yongle period of the Ming Dynasty. Guildhalls flourished during the Jiajing and Wanli periods, reaching their peak in the mid-Qing Dynasty. In the later Ming Dynasty, guildhalls with a commercial and industrial nature emerged, transitioning from simple hometown organizations to business entities.

Teochew merchants, as one of China’s three major business associations, not only conducted business across various provinces within their home province but also ventured far beyond, reaching many countries globally. Consequently, Teochew guildhalls sprouted up worldwide alongside bustling hubs of Teochew business activities.

As the saying goes, “Where there’s the sea, there’s the sound of tides; where there’s the sound of tides, there are Teochew people.” Renowned linguist Lin Lunlun added, “Where there are Teochew people, there are Teochew guildhalls.”

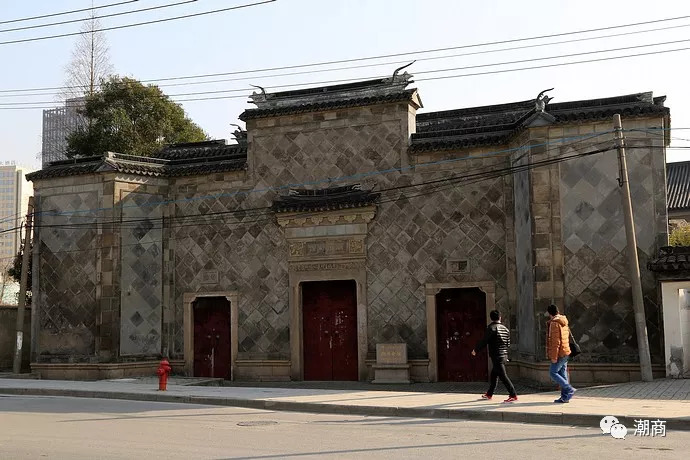

Suzhou Teochew Guildhall

During the Ming Dynasty, Teochew guildhalls were already established, initially in Jinling (present-day Nanjing, Jiangsu Province), and later relocated to Beihao, Suzhou, in the twenty-first year of Kangxi’s reign in the Qing Dynasty.

The Suzhou Teochew Guildhall, established by Teochew merchants from Guangdong during the Qing Dynasty, relocated to Yici Lane, Shangtang, Suzhou (now within Suzhou Fifth High School) in the forty-seventh year of Kangxi’s reign. In the fourth year of Yongzheng’s reign, additional buildings and a stage were constructed. The main hall of the original guildhall prominently featured a portrait of Master Han from Changle, revered by Teochew people. In the eleventh year of Yongzheng’s reign, the Teochew Celestial Palace was added, also known as the Guandi Temple or the Main Hall, dedicated to the deities Guandi, Mazu, and Guanyin. Over the years, it underwent several renovations.

During that period, Teochew merchants in Suzhou mainly dealt in foreign goods, silk fabrics, medicinal herbs, goods from both northern and southern China, marine products, tobacco, pawnbroking, jewelry, jade articles, gold ornaments, silverware, tea, and silver shops. Most of them engaged in transportation, wholesale, and retail businesses, each with their own store numbers in Suzhou.

The Suzhou Teochew Guildhall is one of the best-preserved and most magnificent Teochew guildhalls extant in China. Designated as a cultural heritage site of Suzhou in 1982, it epitomizes the dignified elegance of Teochew culture, narrating the glorious tales of Teochew merchants, an ancient and influential business community.

The guildhall’s main gate and stage are seamlessly integrated, adorned with finely polished square bricks, exuding both elegance and grandeur. The central gate bears the inscription “Teochew Guildhall,” with the left and right side gates bearing the inscriptions “Heqing” and “Haiyan,” respectively, likely carved as prayers for smooth river and sea voyages, reflecting the maritime roots of Teochew merchants. It is said that the guildhall’s main gate once housed two stone lions brought from Teochew, though they are now nowhere to be found.

According to inscriptions, from the forty-seventh year of Kangxi to the forty-first year of Qianlong, the guildhall owned 18 properties, with a total value of approximately 30,665 taels of silver, ranking second among nearly a hundred guildhalls in Suzhou at that time, and particularly outstanding among regional guildhalls.

The Suzhou Teochew Guildhall also has an annex called the “Yin Guildhall,” located in Younong (a place name), serving as a place for Teochew travelers residing in Suzhou to temporarily store coffins. The Yin Guildhall is relatively small, consisting of only seven or eight square-shaped houses designed for convenient coffin placement. Each coffin is placed on specially made long benches, with a place for burning paper money at the entrance. The houses are usually locked, only opened on anniversaries, Qingming Festival, and holidays for relatives to pay respects. Every year, relatives transport coffins back to Teochew for burial. Three days before transporting the coffins, monks are invited to chant scriptures for salvation, while lonely souls who have no one to worship them in the house are worshiped by representatives appointed by the guildhall, comforting the deceased compatriots who died in a foreign land.

The documentary series “The Sugar Road” depicts the footprint of Teochew merchants in Suzhou.

Beijing Teochew Guildhall

The Beijing Teochew Guildhall was built during the Qing Dynasty but primarily served as accommodation for Teochew scholars who came to the capital for imperial examinations.

Teochew people had a tradition of coming to the capital for imperial examinations as early as the Song Dynasty. During the Song, Yuan, Ming, and early Qing Dynasties, Teochew scholars coming to the capital for exams had to stay in guesthouses. However, due to the long duration of the examinations, scholars had to endure poor living conditions in these accommodations. Especially for impoverished scholars, managing expenses was difficult, and in case of illness or death, there was no one to take care of them.

During the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong reigns, with remarkable achievements in culture and martial arts and strong national power, the Qing Dynasty was adept at employing Han Chinese. Teochew people were also honored in both official and non-official positions, with notable figures in the court and outside. However, Teochew intellectuals and military officers who cherished their hometowns, such as Lin Deyong, made multiple efforts to establish Teochew guildhalls to provide accommodation for Teochew scholars coming to the capital for examinations.

As the number of Teochew people going to Beijing for examinations increased, the Teochew Guildhall expanded to three locations: the Southern Guildhall on Yanshou Street, the Northern Guildhall at Haimei Temple in Xuanwumen, and the Western Guildhall in Chengxiang Hutong.

During the Qing Dynasty, many famous officials from Teochew Prefecture stayed at the Teochew Guildhall during the examination period, and many of them, such as Huang Renyong (a first-class imperial guard), Zheng Dajin (a Jinshi scholar who served as the salt commissioner for Lianghuai), Zeng Xijing (a Jinshi scholar who served as the supervisor of the Qing Dynasty’s bank), and Liu Qizhen (a Jinshi scholar who served as the deputy secretary of the imperial council), emerged from humble backgrounds. With a place to stay during their examinations in Beijing, they were able to achieve success and honor.

Whenever there were vacant houses in the three Teochew guildhalls, they would accommodate Teochew visitors and also rent them out to others, with the proceeds going into the guild’s funds.

Shanghai Teochew Guildhall

Yangshuo Road (formerly known as Foreign Firm Street, now 105 Yangshuo Road), located on the outskirts of old Shanghai, near the Sixteen Pu Wharf along the Huangpu River, is where the Shanghai Teochew Guildhall was built in the twenty-fourth year of Qianlong’s reign (1759). Today, there are no traces of the Shanghai Teochew Guildhall on this inconspicuous street, with information about it mainly found in historical records. According to the “Tablet of Chaozhou Guildhall’s Lease Contract,” “In the twenty-fourth year of Qianlong, Zheng Guoliang bought a house in the market, … which was the original site of the guildhall,” indicating that Teochew businessmen traveling to Shanghai had established their own regional organization more than 80 years before Shanghai’s opening as a treaty port.

One of the initiators of the Shanghai Teochew Guildhall was Zheng Jiechen, a tobacco tycoon in late 19th-century Shanghai. Hailing from Chaoyang, he became a leader of the Teochew community in Shanghai by engaging in the legal opium trade, holding a significant position in Shanghai’s opium history. His grandson was Zheng Zhengqiu, acclaimed as the “Father of China’s Film Industry.”

The initial Teochew Guildhall served as a place for Teochew people who left their hometowns to connect with fellow natives and “clan houses.” Over the next two centuries, especially after the opening of Shanghai and Shantou, the trade between the two regions flourished rapidly. Teochew merchants in Shanghai expanded their activities into industries such as sugar, money shops, pawnshops, and spinning, capturing significant market shares. They formed the influential Teochew clique, standing tall alongside the Jiangsu-Zhejiang and Hui cliques. The functions of the Shanghai Teochew Guildhall evolved to include safeguarding the interests of Teochew businessmen, maintaining normal business order, and mediating internal disputes.

becoming a prominent industrialist in modern Shanghai.

In 1912, the Jianghai Customs Tax Office issued new regulations on bonded warehouses, reducing the storage period from two months to fifteen days, which significantly impacted the Teochew clique, whose major professions included sugar, spinning, and general trade. The Shanghai Teochew Guildhall took the lead in protesting, reaching out to allied industries in Yantai through multiple letters to the customs office, seeking support from the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce, ultimately forcing the customs office to compromise.

which were utilized as a horse-keeping facility for the British.

With various requests pouring in, the charitable and public welfare aspects of the Shanghai Teochew Guildhall became increasingly pronounced. In the guild’s archives, there are many records of generous donations from Teochew merchants in Shanghai, assisting disaster-stricken victims in Guangdong and other provinces.

In the first year of the Republic of China, the National Government dispatched personnel to borrow funds from the Shanghai Teochew Guildhall and the Guangzhao Public Hall. After discussions among the guilds’ directors, loans were sent to various businesses in Shanghai, providing strong support to the fledgling National Government. In 1923, shortly after suppressing the Chen Jiongming rebellion, Sun Yat-sen once again wrote to the Shanghai Teochew Guildhall, hoping for “financial assistance.” This personally signed letter by Sun Yat-sen became the most valuable evidence of the Shanghai Teochew Guildhall’s participation in patriotic activities.

From the early years of the Republic of China to the victory of the War of Resistance Against Japan, there were over 200,000 Teochew people in Shanghai, including the writer Feng Kong, the social science scholars Du Guoxiang and Xu Dixin, and pioneers of China’s film industry Zheng Zhengqiu, Cai Chusheng, and Chen Bo’er.

In 1954, the Shanghai Teochew Guildhall was officially dissolved with government approval, and the former Guildhall premises on Foreign Firm Street were handed over to the Haiping Elementary School (later renamed as the First People’s Road Primary School). Today, the former site of the Teochew Guildhall, as part of the overall redevelopment of the southern Bund in Shanghai, will be re-planned and relocated, becoming a new scenic spot along the Huangpu River.

As the saying goes, “One Teochew within the seas, another Teochew overseas.” The continued prosperity of Teochew merchants at home and abroad owes much to the establishment of Teochew guildhalls. Let’s now take a look at several overseas Teochew guildhalls.

Chinese Battle Dance: Puning Nanshan Yingge Wows London in Spectacular Fashion

Chinese Battle Dance: Puning Nanshan Yingge Wows London in Spectacular Fashion  LabCorp hit with federal suit over robocalls

LabCorp hit with federal suit over robocalls  Festive Rush Ignites Production Frenzy in Teochew: Toy Manufacturers Gear Up for New Year Orders

Festive Rush Ignites Production Frenzy in Teochew: Toy Manufacturers Gear Up for New Year Orders  Exploring the Rich Legacy of Teochew Guildhalls: Bridges of Culture and Commerce

Exploring the Rich Legacy of Teochew Guildhalls: Bridges of Culture and Commerce  Renowned Teochew Economist Named Fellow of International Economic Association

Renowned Teochew Economist Named Fellow of International Economic Association